The MTSS Dilemma—Differentiate

at the Grade Level or Remediate at the Student Skill Level?

Dear Colleagues,

[CLICK HERE to Link to the

Full Blog Message]

Introduction

I do a great deal of consulting in middle

schools and high schools across the country helping them to add value to their

multi-tiered system of supports by aligning (a) curriculum and instruction with

(b) assessment and intervention with (c) staff expertise and school resources

directly to (d) students’ skill gaps and proficiency needs.

Sometimes the biggest initial change is to

help schools realize that they have adopted approaches based on principles,

practices, and decision rules that are not psychoeducationally, psychometrically,

or scientifically sound—if though they came from “experts” who appear to be

“expert.”

Many times, sustained success with

academically struggling and social, emotional, and behaviorally challenging

students requires a comprehensive school psychological perspective versus one

depending on leadership, teaching, counseling, or special education.

This is not a competition among

specializations. All teams need

dedicated professionals working together.

This is about the “game plan.” Without a good game plan, many talented teams

do not accomplish—on the field—what they should accomplish given their talent.

Or, metaphorically: While an effective hospital operating room

requires a host of effective, coordinated, and talented professionals, the

operation is successful based on the strengths of everyone understanding their

roles in accomplishing the mechanics of the surgery.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _

When

Secondary Students Have Academic Skill Gaps

A continuing theme, in my secondary-level

consultations, is the instructional dilemma that occurs when students

transition from elementary to middle school—or middle school to high school—and

they haven’t mastered the prerequisite academic skills to succeed at the next

grade level.

While this occurs most often in the areas of

English, reading, and literacy, or mathematics, calculation, and numeracy, we sometimes

forget the impact on students’ learning when they are also unprepared to

effectively write or to communicate verbally at their grade levels.

And then there are the “lateral effects” when

students’ low literacy or mathematics skills negatively impact their learning

and performance in science, the social sciences, or in other transdisciplinary

areas.

In Part I of this two-part Blog

series, we will discuss (a) the options available to schools to address these

students’ needs; (b) how to determine which options are needed; and (c) how to

courageously recognize (and enact) the one option that schools most avoid.

In Part II, we will review and apply

the results of two national research studies, published this week, that address

the impact of teaching secondary students—who are significantly behind in their

foundational math skills—in grade-level courses or in skill-level courses.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _

Students

with Significant Academic Skills Gaps: Connecting Their Needs to Closing-the-Gap Options

From a multi-tiered perspective, a

data-based problem-solving process is needed to quantify, analyze, and

hopefully close any academic gaps that occur at the secondary level. Just like the diagnostic process that a

doctor completes when you are sick—before prescribing the medicine and other

facets of your medical intervention, data-based problem-solving is a necessity

if we are going to implement effective, high-probability-of-success academic

interventions.

Unfortunately, many schools have some data,

but it is descriptive and not diagnostic data. And then they use these data to inadvertently

play “intervention roulette”—throwing “interventions” at problems without

really knowing the root causes as to why they exist.

I am critiquing, not criticizing, these

schools. More often than not, they are

doing what they were told to do by their “experts.”

_ _ _ _ _

But, critically, at the point of

intervention, there still are times when schools hit the proverbial “fork

in the road.”

This occurs, specifically, when students’

prerequisite academic skills are so low that everyone knows that they have

virtually no chance of passing the next middle or high school course.

Here, most schools use one of the following

Options:

- Option 1. Schools schedule the “not-ready-for-prime-time” students into their existing course sequences, and teach them at their grade levels— hoping that effective differentiated instruction will close the existing achievement gaps at the same time that the students learn and master the new, course-related content and skills?

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 2. Schools use Option 1—scheduling the “not-ready-for-prime-time” students into their existing course sequences, and then they offer/provide tutors or tutoring (usually before or after school) to supplement the instruction and “close” the gaps.

This, unfortunately, rarely works because (a) the

students are too far behind to benefit from tutoring—that is, there simply is

not enough time available to close the long-standing gaps; (b) the tutoring is

provided by paraprofessionals who do not have the expertise to implement the

strategic interventions needed; (c) the tutoring is not coordinated with the general

education teachers or aligned to the curricula being taught in the core

classes; and/or (d) the student does not attend the tutoring (enough) due to

transportation, studying for other classes, extracurricular activities, or

simply fatigue, frustration, or resignation.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 3. Schools “double-block” the students—scheduling them into the existing course sequences while also giving them an additional academic period a day (or less) to remediate their skills gaps.

Here, they are hoping that the remediation period will

“catch the students up,” while they simultaneously complete the grade-level

courses so they can accrue their credits.

But many times, the teachers teaching these two separate courses do not

communicate, the curricula and interventions are not coordinated, and the

students still do not have the skills to pass the grade-level course.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 4. Here, schools “double-block” the students, but the students have the same teacher for both blocks. This allows the teacher to follow the grade-level course’s syllabus, but s/he can spend time remediating students’ prerequisite skills gaps so they are prepared for and can learn and master the grade-level course material.

In addition, this also gives the teacher the time needed

to adapt his or her instruction for students who require, for example, (a) more

concrete and sequential instruction, (b) more positive practice repetition, or

(c) assistive supports or accommodations to learn the material.

In reality, based on their data-based

student analyses, schools may be well-advised to have Options 1, 3, and 4

available in order to maximize the learning and mastery of different students

with different learning histories and instructional needs.

[This is not to say that Option

2—Tutoring is not needed for students with more narrow skill gaps. And, obviously, the teachers in Option 3 need

to coordinate the curriculum, instruction, and interventions in order to attain

the strongest student outcomes.]

_ _ _ _ _

But to determine the need for these

different Options, and to fully prepare for their implementation, effective schools

typically complete and pool the data-based student analyses by March or

April before the next academic year.

This gives them the time to judiciously coordinate the services,

supports, courses, instructors, and scheduling needed by same-grade groups of

students.

While making the recommendation

immediately above (even as March is still six months away), I understand

that all schools have too many immediate and long-term needs already on their

plates. . . and that some colleagues may dismiss this recommendation as either

unrealistic or not (currently) a high priority.

But I would respectfully suggest that many

of my colleagues’ immediate and long-term needs already center around the

academic, behavioral, attendance, or graduation status of the students that we

are discussing.

Moreover, I know (because we have facilitated

this in schools nationwide) that this recommendation can be accomplished

when schools recognize the importance of personalizing their instruction and

intervention, and evaluating and upgrading their multi-tiered systems of

support.

But this all requires strategic planning,

staff readiness and flexibility, and effective resource management. And, this can be accomplished in the

next six months.

For small, budget-stressed, and/or

staff-limited schools, I also understand the challenges embedded in the

recommendation above. But when the

data-based problem-solving process is used, at least we know the cumulative student

skill gaps that are present, and which groups of students need what

approaches.

At this point, we realistically connect as

many “dots” as we can—maximizing existing resources, and impacting as many

students as possible. We then plan for

the additional dots that we will connect the next year.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _

Middle

Schools, High Schools, and Stark Realities

Critically, in our experience, middle schools

(if they choose to take it) have more flexibility to “schedule around” their

students, staff, and courses than high schools—especially when the latter are

not allowed (usually, by their state education codes) to give course credit for

“remedial” courses.

Indeed, if middle schools know the academic

and behavioral status of their rising 6th graders in April or May, they can

align their students, staff, and courses to flexibly meet the needs of

different clusters of students—from those entering with significant academic

skill gaps, to those whose academic skills already exceed the 6th grade courses

they might “repeat.”

With all due to respect, on behalf of the

students with significant skills gaps, here is a stark reality: Middle School credits don’t count.

That is, if middle school students with

significant academic skill gaps “pass” their courses, but do not master the

“elementary” and “middle school” skills that they need, we have simply

passed the “problem” on to the high school “to solve.”

The

recommendation, then, is to focus on foundational academic skills (in literacy,

math, oral expression, and written expression), and students’ mastery of those

skills. And if—for students with

significant skill gaps—we need to go “backwards to go forward,” or to go “slow

in order to go fast,” then do it.

The Mission: Prepare these students

in middle school for high school. Gaps

in information and content can always be addressed as long as there are no gaps

in foundational skills and mastery.

_ _ _ _ _

But there are comparable “stark realities” in

high school when students with significant skills gaps are present there. . .

leading up to an Option 5:

- Just as many students do not complete their college programs in four years, perhaps some students need more than four years of high school in order to learn and master the skills and content needed to be college and/or career ready.

Indeed, for states and high schools that are moving to

competency-based academic systems (e.g., New Hampshire), this is a natural

outcome.

[Parenthetically: These systems also produce “three-year

graduates” who are ready for dual-enrollment courses or college because they have

demonstrated their comprehensive high school proficiency by their junior years.]

[Also, parenthetically: The reason why some college students need more

than four years to graduate is because they are taking remedial courses

during their freshmen years to make up for their high school deficiencies.]

[Finally, parenthetically: Why is it that some states have no problem

retaining students in Grade 3—when they have not mastered their reading skills,

and yet they “penalize” high schools when they do not graduate their students

in four years?]

In the final analysis, as in Middle School,

“passing” courses and “graduating” from high school is irrelevant if students do

not have the summative academic and related skills to truly succeed at the

“college and/or career level.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _

So . . .

Secondary Schools Need to Consider Option 5

Given the discussion above, middle and high

schools need to consider (and the U.S. Department of Education, and the

respective State Departments of Education, need to allow) an Option 5.

Option 5 is for students who have no

chance of passing their next middle or high school course even using Options 1,

3, or 4 above—because their prerequisite academic skills are so low. This appraisal is based (see below) on

objective, multi-instrument, diagnostic skill gap analyses of each struggling

student—conducted at the relevant secondary school level.

Thus, the school’s multi-tiered

system must include (a) a data-based problem-solving process to determine the

root cause(s) of the students’ learning and/or skill gaps; and (b) an Option

5 configuration where the instructional and intervention approaches needed

to close the respective students’ skill gaps can be delivered with integrity

and intensity.

Critically, for

students who do not have a disability and, therefore, who do not qualify for

services through an Individualized Education Plan (IEP; IDEA) or a 504 Plan (Section

504 of the Rehabilitation Act), Option 5 may be the best option.

What is Option 5?

- Option 5 involves scheduling students into a course (or a double-blocked course) in their academic area(s) of deficiency that targets its focus and instruction on the students’ functional, instructional skill level. That is, the course takes students from their lowest points of skill mastery (regardless of level), and moves them flexibly through the each grade level’s scope and sequence as quickly as they can master and apply the material.

This should be an

instructional—not a credit recovery or computer/software-dependent—course

with a teacher qualified both in instruction and intervention.

Moreover, this is

the students’ only course in the targeted academic area, and the course

instructors are responsible for making the content and materials relevant to

the grade level of the student, even as they are teaching specific academic

skills at the students’ current functional skill levels.

Thus, students are not

concurrently taking a grade-level course in the same academic area (as in

Options 1 through 4 above). In addition,

the teachers in these students’ science, social science, or other courses also

know the students’ current functional skill levels—differentiating their

instruction as needed, while providing additional supports, so that the

students’ areas of academic weakness do not negatively impact their learning in

these “lateral” courses.

_ _ _ _ _

For example, if a

group of rising 9th grade students have mastered their math skills only at the

beginning fourth grade level, their Option 5 math class for that quarter,

semester, or year would begin its instruction at the fourth grade level of the

state or district’s preschool through high school math scope and sequence, and

progress accordingly as a function of their learning and mastery.

The students would

not concurrently take a 9th grade math course, and the Option 5 teachers

would be responsible for making the math content and materials relevant to a

9th grade learner, even as the mathematical skills are being taught at a 4th

grade level.

In reading, the Option

5 teachers would use, for example, high-interest (9th grade content and focus)/low

vocabulary (4th grade) books, stories, or materials so that the students can

build their vocabulary and comprehension skills in a sequential and progressive

way.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A Deeper Dive on Which Students Would Benefit from

Option 5

There are a number

of possible (combinations of) reasons why rising-secondary students transition from elementary to middle

school—or middle school to high school—without the prerequisite academic skills

to succeed at the next grade level. These reasons are identified through the

data-based root cause analysis process that begins by collecting information

that chronicles each individual student’s current status and past educational services,

supports, programs, interventions, accomplishments and experiences.

Indeed, at the beginning of a root cause

analysis for an individual student, the initial information-gathering

activities are called the “First Things First.”

[CLICK HERE to Link to the

Full Blog Message that Fully Describes these Important Initial

Information-Gathering Activities]

_ _ _ _ _

The information from the First Things First

help to identify a student’s (a) strengths, skills, assets, and existing

supports; (b) weaknesses, skill gaps, limitations, and negative life events and

circumstances; and (c) educational history and experiences, including the

quality of past teachers and instruction, the presence of sound curricula and

interventions (when needed), and the engagement and motivation of the student

when present in school.

_ _ _ _ _

Focused then on determining why a

student’s specific skill gaps exist, the root cause analysis typically

continues by completing diagnostic assessments on how the student best learns,

and functional assessments targeted to confirming (or rejecting) hypotheses

that similarly relate to past, and that now relate to predicting present,

student learning.

For students with significant academic

skill and mastery gaps at the secondary level, the most common root causes

include the following.

[CLICK HERE to Link to the

Full Blog Message Describing these Common Causes in Detail]

_ _ _ _ _

The vast majority

of these root causes point to the fact that students who will most benefit from

an Option 5 approach are students who did not have the opportunity to

originally learn and master the academic skills that are now embedded in their

significant skill gap.

At the same time,

many of these student will need additional social, emotional, or behavioral

services and supports so that the academic interventions can be successful.

Even more

critically, the student’s motivation and positive, active engagement in the

Option 5 course(s) and classroom will be a key factor in determining success. This will be especially true at the high

school level, when students are confronted with the reality of a four-plus year

high school career (which may look worse than dropping out, or going for a

GED).

All of this is to

say that not all students who could potentially benefit from an Option 5

approach should or will choose it. For

Middle School students, the Option involves less student choice, and more

“pressure” on the school to keep the students well-integrated with their peers

and in other grade-level classes. For

High School students, they need to see realistic ways that they can pass their

high school courses after or as their skill deficits are remediated.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A Continuum of Academic Supports and Interventions

From both a

prevention and a strategic intervention perspective, schools need to recognize

the services, supports, strategies, and interventions available along a

multi-tiered continuum.

In a past Blog, we

differentiated among services, supports, strategies, and interventions. Relative to the latter, we identified the

following key elements of interventions:

- Interventions are intentional and focused on changing an academic or social-emotional skill or behavior.

- Interventions involve a specific program or set of formalized steps required for implementation and proven to effect change.

- Interventions are specific and formalized. An intervention lasts a certain number of weeks or months, is reviewed at set intervals, and has demonstrable short- and long-term outcomes.

- Interventions are implemented with formal evaluation approaches that track and measure students’ progress.

We also provided

some examples:

- Tutoring is a service; the specific academic interventions used by a trained and skilled tutor is the intervention.

- Counseling or psychotherapy is a service; the therapy that a psychologist uses (e.g., cognitive-behavior therapy) is the intervention.

- A sensory “time-out” for a student experiencing trauma is a support; the strategies or therapies that a student received to eliminate the need for future time-outs is the intervention.

[CLICK

HERE to Link to Blog:

February 16, 2019 Redesigning Multi-Tiered

Services in Schools: Redefining the Tiers and the Difference between

Services and Interventions

_ _ _ _ _

The point here is

that Option 5 will only succeed if the best services, supports,

strategies, and interventions are matched to the root causes that explain

why secondary students have such significant academic skill gaps.

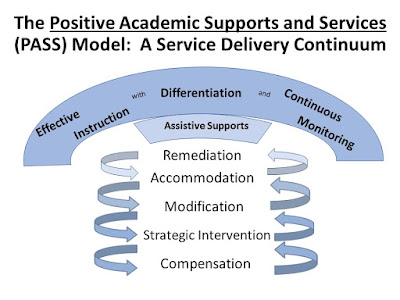

To expand this

discussion, below are the key components of our Positive Academic Supports

and Services (PASS) continuum. . . a science-to-practice blueprint that, in

the context of the current discussion, is tailored to each individual student’s

needs (see the Figure below).

Overview. The foundation to the PASS blueprint is

effective and differentiated classroom instruction where teachers use and

continuously evaluate (or progress monitor) evidence-based curricular materials

and approaches that are matched to students’ learning styles and needs. When students are not consistently learning

and mastering academic skills after a reasonable period of effective

instruction, practice, and support, the data-based, functional assessment,

problem-solving process is used to determine the root causes of the

problem.

Results then are

linked to different instructional or intervention approaches that are organized

along the following PASS continuum.

[CLICK HERE to Link to the

Full Blog Message for a Detailed Description of the PASS Components]

_ _ _ _ _

While there is a

sequential nature to the components within the PASS continuum, it is a

strategic and fluid—not a lock-step—blueprint.

That is, the supports and services are utilized based on students’ needs

and the intensity of these needs. For

example, if reliable and valid assessments indicate that a student needs

immediate accommodations to be successful in the classroom, then there is no

need to implement remediations or modifications just to “prove” that they were

not successful. In addition, there are

times when students will receive different supports or services on the

continuum simultaneously. For example,

some students will need both modifications and assistive supports in order to

be successful. Thus, the supports and

services within the PASS are strategically applied to individual students.

Beyond this, while

it is most advantageous to deliver needed supports and services within the

general education classroom (i.e., the least restrictive environment), other

instructional options could include co-teaching (e.g., by general and special

education teachers in a general education classroom), pull-in services (e.g., by

instructional support or special education teachers in a general education

classroom), short-term pull-out services (e.g., by instructional support

teachers focusing on specific academic skills and outcomes), or more intensive

pull-out services (e.g., by instructional support or special education

teachers).

These staff and

setting decisions are based on the intensity of students’ skill-specific needs,

their response to previous instructional or intervention supports and services,

and the level of instructional or intervention expertise needed. Ultimately, the goal of this effective school

and schooling component, and the PASS model, is to provide students with early,

intensive, and successful supports and services that are identified through the

problem-solving process, and implemented with integrity and needed intensity.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

This Blog focused on the instructional

dilemma that occurs when students transition from elementary to middle

school—or middle school to high school—and their academic skill levels are so

low that (a) they have no hope of learning or succeeding in the courses at the

next grade level, and (b) their skill gaps are so significant that the

different remedial options that most schools use will not close the gaps.

During the discussion, the four Options that

most middle or high schools use to address this dilemma were described—noting

their differential strengths and weaknesses, and how schools miss (or ignore)

the fact that these options will not address these students’ significant needs.

We then detailed a number “stark realities”

that we summarized in the following ways:

- If middle school students with significant academic skill gaps “pass” their courses, but do not master the “elementary” and “middle school” skills that they need, we have simply passed the “problem” on to the high school “to solve.”

- Moreover, if these students “pass” courses and “graduate” from their high schools without mastering the academic and related skills needed to truly succeed at the “college and/or career level,” the schools have not accomplished their educational mission and a disservice has been done to the students.

From a multi-tiered perspective,

then, the goal is to complete (a) a data-based problem-solving process that

links the results of a root cause analysis to strategic or intensive services,

supports, strategies, and interventions; and (b) to consider a fifth option

where students are taught at their functional skill and mastery levels, and

where they receive the interventions and supports needed to learn, master, and

progress through the academic skills needed to ultimately be successful at

their true grade levels.

More specifically,

this Option involves scheduling students into a course (or a double-blocked

course) in their academic area(s) of deficiency that targets its focus and

instruction on the students’ functional, instructional skill level. That is, the course takes students from their

lowest points of skill mastery (regardless of level), and moves them flexibly

through the each grade level’s scope and sequence as quickly as they can master

and apply the material.

This course is the

students’ only course in the targeted academic area, and the course

instructors are responsible for making the content and materials relevant to

the grade level of the student, even as they are teaching specific academic

skills at the students’ current functional skill levels.

Thus, students are not

concurrently taking a grade-level course in the same academic area. In addition, the teachers in these students’

science, social science, or other courses also know the students’ current

functional skill levels— differentiating their instruction as needed, while

providing additional supports, so that the students’ areas of academic weakness

do not negatively impact their learning in these “lateral” courses.

_ _ _ _ _

Complementing the

discussion above, the Blog next described the initial information-gathering

steps of the data-based problem-solving process, and then the primary reasons

why students would enter their secondary school careers with significant

academic skill deficits. The Blog

finished by outlining the components of the multi-tiered Positive Academic

Supports and Services (PASS) system—a science-to-practice continuum of

services, supports, strategies, and interventions for academically struggling

students.

The ultimate goal for students with significant

skill deficiencies is to close their skill gaps with mastery-based learning as

quickly as possible, so that they can then learn and master the skills in their

grade-level courses and, ultimately, graduate success-ready for college and/or

their careers.

While the recommended approaches for these

students may be controversial or challenging, with good strategic

planning—completed in March or April of the school year before implementation—they

can be accomplished.

Indeed, once the data-based problem-solving

process is used to analyze these students, at least we then know the depth and

breadth of the skill gaps that are present, and which groups of students

need what approaches.

At this point, schools can realistically

connect as many “dots” as possible— maximizing their existing resources, and

impacting the greatest number of students.

They, then, can connect the next series of dots the next year . . . and

so on.

_ _ _ _ _

In Part II of this Blog series, we

will review and apply the results of two national research studies, published

this past week, that address the impact of teaching secondary students—who are

significantly behind in their foundational math skills—in grade-level courses

or in skill-level courses. This research will reinforce the recommeseider.

Meanwhile, I appreciate your ongoing

support in reading this Blog. As always,

if you have comments or questions, please contact me at your convenience.

And please feel

free to take advantage of my standing offer for a free, one-hour conference

call consultation with you and your team at any time.

Best,

Howie