Behind Every Iron Chef is

an Iron-Clad Recipe

[CLICK HERE for the Full Blog Version of this Discussion]

Dear Colleagues,

I tell a student that the

most important class you can take is technique. A great chef is first a great

technician. 'If you are a jeweler, or a surgeon or a cook, you have to know the

trade in your hand. You have to learn the process. You learn it through endless

repetition until it belongs to you.

Jacques Pepin

Introduction

Cloaked in subdued anxiety, I am

actually writing this from an airplane—my first business trip (to California

and New Mexico) in eighteen months.

Leaving behind the virtual world

(for now), I am looking forward to helping four schools prepare—not just for

the troubling effects of the pandemic on their students’ social, emotional, and

behavioral health—but for the issues that also were present before COVID-19.

One of these pre-pandemic issues

involves helping teachers, staff, and administrators to better understand the

behavior of students of color. Too often, when these students demonstrate

“inappropriate” behavior, they are viewed as “discipline problems.”

When educators understand the

historical, cultural, sociological, and psycho-educational “make-up” of

students of color, they more accurately contextualize and respond to their

“inappropriate” behavior.

[Please note the quotation marks

above.]

One of the challenges here is getting teachers

and administrators to see their place in the decades-old national problem where

students of color are disproportionately sent to the principal’s office for

“discipline,” and then disproportionately suspended or placed in alternative

programs by their administrators.

This problem often includes

teacher referrals and administrative placements for behaviors that are dealt

with in the classroom for White students, but responded to more punitively for

students of color.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

An Overview of Part I in this Series

This two-part Blog Series is

dedicated to helping districts and schools to successfully eliminate

disproportionate discipline referrals and (punitive) actions for students of

color.

In Part I of the Series, we

presented a definition of “racism,” and talked about Critical Race Theory. We

did this to emphasize that (a) the disproportionate disciplinary treatment of

students of color—especially Black students (as well as students with

disabilities)—has existed for decades, and that (b) initiatives to eliminate

disproportionality should not be linked to the recent politicized

conversation involving Critical Race Theory.

Relative to the latter area, we

objectively reviewed the current information regarding Critical Race Theory and

its presence in America’s classrooms. We also expressed concerns about the

impact that legislative and other policy-level actions—focused on restricting

or eliminating the discussion of Critical Race Theory in schools—might have on

teachers and students.

[CLICK HERE to Read Part I]

In the end, with citations, we

documented:

- The political nature of the Critical Race Theory legislation

in a number of states;

- The fact that most teachers are not teaching this theory in

their classrooms;

- Concerns that schools are going to be wasting a lot of time

this year on Critical Race Theory discussion, debate, professional development,

lesson plan analysis, and administrative supervision (to ensure that teachers

understand and do not include Critical Race Theory in their classrooms)— because

of the legislation and/or because of misinformation in many communities; and we

documented

- The additional implications relative to teacher trust,

academic freedom, and the potential that legitimate classroom instruction and

discussion on race, racism, equity, and Black history will be reduced,

sanitized, or eliminated because teachers are afraid either to be unjustly

accused of teaching Critical Race Theory, or to trigger undue student

controversy or emotions.

Based on the information

presented in Part I, we recommended that educators avoid wasting their time by

looking past the Critical Race Theory politics and debate and, instead, focus

directly on how to eliminate the disproportionate disciplinary referrals and

actions against students of color—a long-standing result of racial bias in our

schools.

Part I then discussed the

different approaches that have been implemented in the past to address

school-level disciplinary disproportionality—explaining why they have not

worked and, hence, why they should be avoided in the future.

This presentation was organized by

describing six Reasons or Flaws:

Reason/Flaw #1.

Educational leaders have tried to change the disproportionate numbers through

policy and not practice.

Reason/Flaw #2. State

Departments of Education (and other educational leaders) have promoted

whole-school programs that are unproven or have critical scientific flaws.

Reason/Flaw #3. Districts

and schools have implemented frameworks that target conceptual constructs,

rather than instruction that teaches social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Reason/Flaw #4. Districts

and schools have not recognized that classroom management and teacher training,

supervision, and evaluation are keys to decreasing disproportionality; and they

are depending on Teacher Training Programs to equip their teachers with

effective classroom management skills.

Reason/Flaw #5. Schools

and staff have tried to motivate students to change their behavior when they

have not learned, mastered, or are unable to apply the social, emotional, and

behavioral skills needed to succeed.

Reason/Flaw #6. Districts,

schools, and staff do not have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to

implement the multi-tiered (prevention, strategic intervention, intensive

need/crisis management) social, emotional, and/or behavioral services,

supports, and interventions needed by some students.

[CLICK HERE to Read Part I]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

An Overview of Part II in this Series

In this Series Part II, we

respond to the six reasons/flaws above by providing effective practices and

solutions to decrease or eliminate disproportionality.

As part of this discussion, we

directly address an embedded issue in many of the race-based laws passed by

different states during this year’s legislative sessions.

In a July 14, 2021 Education

Week article, “Four Things Schools Won’t Be Able to Do Under ‘Critical Race

Theory’ Laws,” it was noted:

In

recent years, some school districts with shifting racial demographics have

launched multi-pronged efforts to better serve students of color. They’ve

formed diversity, inclusion and equity committees made up of students,

teachers, and administrators, hired equity officers, and offered ongoing

training for teachers to recognize and rid themselves of their unconscious

biases, which many experts argue lead to, among other things, disproportionate

suspensions and expulsions, for Black and Latino students.

Now,

in at least nine states (e.g., Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa), those efforts, advocates

and district administrators say, would effectively come to a halt.

[CLICK

HERE for Article]

We clearly believe that staff who

are specifically motivated by explicit bias and overt prejudice should be held

directly accountable for discriminatory behavior. This has not changed due to

the recent state legislation.

However, we also recognize

that—even if it were permitted—“ongoing training for teachers to recognize and

rid themselves of their unconscious biases” has largely not worked.

[See our December 5, 2020 Blog:

“Training Racial Bias Out of Teachers: Who Ever Said that We Could? Will the

Fact that In-Service Programs Cannot Eliminate Implicit Bias Create a Bias

Toward Inaction?”

CLICK

HERE to Link]

So, at least on this level, the

recent state legislation in this area should not dramatically impact school and

districts’ effective efforts to decrease and eliminate disciplinary

disproportionality.

And yet, this still is not

occurring in so many districts and schools because, as discussed in Part I of

this Blog Series, many have focused their efforts in one or more of the six

Reason or Flaw areas above... and many are not using the scientific,

psychoeducational components that do not involve racial anti-bias training,

and that do involve essential and proven field-tested practices.

Thus, in this Blog, we will:

- Describe five interdependent psychoeducational components

and their specific, embedded practices (addressing Flaw #1); that are

- Organized within a strategically-implemented,

evidence-based, multi-tiered professional development and coaching-centered

whole-school initiative (addressing Flaw #2); that focuses on

- Teaching students—from preschool through high

school— specific, observable, and measurable social, emotional, and behavioral

self-management skills (addressing Flaws #3 and 5).

- We then advocated the use of a data-based

problem-solving process—when students demonstrate frequent, persistent,

unresponsive, significant, or extreme levels of inappropriate, disruptive,

unpredictable, antisocial, or dangerous behavior—to objectively identify the

root causes of the behavior, and to discriminate discipline problems from

social, emotional, behavioral, and/or mental health problems. . . so that

- The assessment results can be linked to the

strategic or intensive multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, or

interventions that will eliminate the student problem and replace it—once

again—with appropriate behavior (addressing Flaw #6).

While this Blog will primarily

focus on student outcomes, note that we provided an extensive discussion in

Part I of this Series addressing the fact that some teachers, staff, and

administrators are complicit in the disproportionate office referral and school

suspension numbers when they (re)act due to a lack of (student and racial) knowledge

and information, understanding and analysis, skill and application, motivation

and self-reflection, entitlement and privilege, or prejudice and bias.

To address these professional (or

unprofessional in the case of prejudice and bias) gaps, we recommended

district- and school-level training, coaching, supervision, and evaluation as

keys to decreasing disproportionality (addressing Flaw #4).

[CLICK HERE for the Full Blog Version of this Discussion]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Solving the

Disproportionality Dilemma

This Blog began with a quote from

a Master Chef discussing the importance of (over-)learning the techniques

needed to prepare a world-class meal.

Expanding on this analogy by reflecting

on the title of this Blog, good technique—which involves process, must

be complemented by a good recipe—which involves substance (i.e., the

ingredients) and sequence (i.e., the step-by-step implementation).

Applying this to eliminating

disproportionality, schools need to have both a proven recipe for change, and

the complementary processes needed to prepare the recipe with intent and

fidelity.

A major principle grounding the

disproportionality recipe is:

- When all students (including students of color) are taught

(in developmentally, culturally, and pedagogically-sound ways—from preschool

through high school), and when they have mastered and can apply specific and

scaffolded interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution,

and emotional control, communication, and coping skills. . . and

- When they are prompted, motivated, and held accountable for

using these skills in all school settings and circumstances. . .

- They will consistently demonstrate appropriate, prosocial

interactions. . . such that

- The need to need a disciplinary referral to the principal’s

office will become moot.

Critically, and as acknowledged

earlier, some students will need multi-tiered strategic or intensive services,

supports, strategies, or interventions in order to learn and demonstrate their

social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

To determine these services and

supports, data-based analyses should be conducted to determine why the students

are not learning or performing so that, like a Master Chef, modifications to

the recipe can occur—still resulting in a world-class meal.

_ _ _ _ _

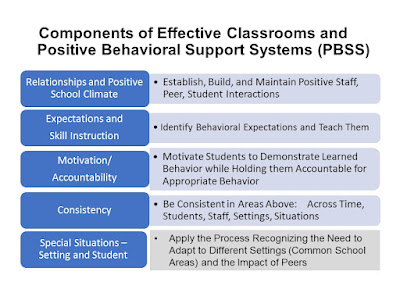

At the center of the

disproportionality recipe are five interdependent components that have an

assortment of important practices within them (see the Figure below).

From:

Knoff, H.M. (2014). School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management: A Positive Behavioral Support Implementation Guide.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

CLICK HERE for more information.

These components are:

- Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climates

- Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skill Instruction

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

They are briefly described below.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

Effective schools work

consciously, planfully, and on an on-going basis to develop, reinforce, and

sustain positive and productive relationships so that their cross-school and

in-classroom climates mirror these relationships.

Critically, however, these

relationships include the following interactions: Students to Students, Students to Staff,

Staff to Staff, Students to Parents, and Staff to Parents.

Relative to minority students, these

interactions involve understanding them, their backgrounds, their personal and

familial histories, their strengths and weaknesses, and their personal or

unique stories or experiences.

For minority students, this also

includes understanding their racial and cultural backgrounds, but care is

needed not to stereotype these backgrounds such that individual students are

not seen as individuals.

Positive relationships and

school/classroom climates result when all of the adults in a school actively

participate. But the students are also part of this process, as well as the

different formal and informal peer groups, clubs, and organizations represented

across the school.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

All students from preschool

through high school—including students of color—need to be explicitly taught

(just like an academic skill) the explicit social, emotional, and behavioral

expectations in their classrooms and across the common areas of the school. These

expectations need to be communicated in a positive, prosocial—rather than a

negative, deficit-oriented—way. That is, students need to be taught “what to

do,” rather than “what not to do.”

Indeed, teachers and

administrators will have more behavioral success teaching and prompting

students, for example, to (a) walk down the hallway (rather than “Do not run”);

(b) raise your hand and wait to be called on (rather than “Do not blurt out

answers”); or (c) accept a consequence (rather than “Don’t roll your eyes and

give me attitude”).

In addition, these expectations

need to be behaviorally specific—that is, we need to describe exactly what specific,

observable steps we want students to perform—for example:

- Walk onto the bus

quietly, using social distancing;

- Sit in the first

open seat and move all the way in;

- Put your books on

your lap or your bookbag under the seat in front of you;

- Talk only with

your neighbors using a whisper or conversational voice; and

- Stay seated until

the bus has stopped, and it is your turn to leave.

Indeed, it is not instructionally

helpful to talk in constructs—telling students that they need to be

“Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.” This is because each

of these constructs involve a wide range of undefined behaviors. Moreover, at

the elementary school level, students really do not functionally or

behaviorally understand these higher-ordered constructs. At the secondary

level, meanwhile, students often interpret these constructs (and their many

inherent behaviors) very differently than staff.

Thus, and as above, we need to

teach students the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention

and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills that we

want them to demonstrate at each grade and developmental level.

Moreover, we need to teach these

skills the same way that successful basketball coaches teach the plays in their

playbooks. That is, we need to (a) teach students the specific steps for each

social skill, along with the related behaviors; (b) positively demonstrate the

steps to them in meaningful and real-life scenarios; (c) give students structured

opportunities to practice each skill in simulated roleplays with guidance and explicit

feedback; and then (d) help students to apply (or transfer) their new skills more

automatically and independently to “real-world” situations.

Embedded in this instruction is

the social problem-solving needed to select the best behavioral choices for

different situations. Also included is how to maintain self-control when faced

with emotional triggers and stress, peer pressure and conflict, or other home

or school disruptions.

Significantly, there are hundreds

of important social, emotional, and behavioral skills that could be taught

during students’ school careers. Examples of some needed social skills include:

Listening, Following Directions, Asking for Help, Ignoring Distractions,

Dealing with Teasing and Bullying, How to Accept a Consequence, How to Deal

with Losing or Not Getting Your Own Way, How to Handle Peer Pressure and

Rejection, How to be a Good Leaders and a Good Team Member, How to Set Goals

and Develop Good Action Plans.

All of the core social skill

instruction is led by general education teachers. This is because (a) they know

the students better than anyone else; (b) they have more opportunities to

prompt, practice, reinforce, and correct the skills in real-life classroom

situations; (c) they need to use these skills to facilitate classroom

management and positive school climates; and (d) they need to integrate these

skills into students’ academic engagement and success.

For students who need modified,

small group, or individual (cognitive behavior therapy-based) instruction

(e.g., at the Tier 2 or Tier 3 levels), this is done by school or school-based

mental health staff—counselors, psychologists, or social workers.

Relative to disproportionality,

when students of color learn these skills, routines, and interactions—in

developmentally, culturally, and pedagogically-sound ways, they will more consistently

demonstrate appropriate, prosocial interactions, and there will be less (no)

need for discipline.

_ _ _ _ _

Student Motivation and Accountability

For the skill instruction

described above to “work,” minority students need to be motivated to and held

accountable for demonstrating positive and effective social, emotional, and

behavioral skills.

Scientifically, motivation is

based on two component parts:

Incentives and Consequences.

But to work, these incentives and

consequences must be meaningful and powerful to the students (not

just to the adults in a school).

That is, too often schools create

“motivational programs” for students that involve incentives and consequences

that the students couldn’t care less about. Thus, the programs look good “on

paper,” but they hold no weight in functional, behavioral reality—at least from

the students’ perspectives.

But this is not about motivational

programs, it is about effective practices.

And in order to decrease or

eliminate disproportionality, while increasing effective classroom management and

student self-management practices, teachers need a classroom discipline “road

map.”

For us, we call this road map the

Behavioral Matrix, and we work constantly with schools nationwide to

help them develop their own grade-level Matrices that are sensitive to and reflective

of their staff and students.

The Behavioral Matrix is

the “anchor” to a school’s behavioral accountability and progressive school

discipline system. At the Elementary School level, there typically is a

Behavioral Matrix at each grade level because of the developmental differences

across prekindergarten through (typically) Grade 5 students.

At the Secondary level, there

typically is a school-wide (for example, Grade 6 to 8, and Grade 9 to 12)

Matrix for each middle and high school, respectively. Significantly, at times

these schools create separate Grade 6 and Grade 9 matrices, because these

students are often entering their middle or high schools, respectively, for the

first time, and the schools want to individualize the behavioral expectations

and accountability attention specifically to them.

Every Behavioral Matrix

has quadrants that address appropriate versus inappropriate behavior,

respectively (see the Figure below). The first two quadrants of the Matrix

specify (a) the behavioral expectations in the classroom connected (b) with

positive responses, motivating incentives, and periodic rewards.

The third and fourth quadrants,

respectively, identify four progressive “Intensity Levels” of inappropriate

behavior, connected with research-based responses and strategies that

facilitate a change of this inappropriate behavior.

When teachers and

administrators use these quadrants with fidelity, they help to eliminate both

disproportionate referrals of students of color to the principal’s office, and repeated

school suspensions of the same students—especially, when multi-tiered services

and supports are in order.

When students are taught, as recommended,

about the different levels of inappropriate behavior and how each level will be

addressed, many (a) are motivated to avoid these responses by demonstrating

appropriate behavior, or (b) are not surprised by the teacher consequences or

administrative responses that occur when they choose to demonstrate

inappropriate behavior.

In addition, many students

internalize the Matrix, and it becomes an internal, intrinsic self-management

guide that facilitates self-control, behavioral decision making,

self-reinforcement, and self-accountability.

When teachers are involved

in creating and/or are taught to use the Matrix as part of their classroom

management, they realize that (a) Intensity I or II inappropriate student behaviors

should not be sent to the principal’s office, and (b) there will be

administrative questions, training, coaching, or even personnel-related actions

if they continue to send Intensity I or II behavior to the office.

The four Intensity Levels are

briefly defined as follows:

Intensity

I (Annoying) Behavior: Behaviors in the classroom that are

annoying or that mildly interrupt classroom instruction or student attention

and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a minimum of interaction

by using a corrective response (e.g., a non-verbal prompt or cue, physical

proximity, a social skills prompt, reinforcing nearby students’ appropriate

behavior).

_

_ _ _ _

Intensity

II (Disruptive or Interfering) Behavior: Behavior problems in

the classroom that occur more frequently, for longer periods of time, or to the

degree that they disrupt classroom instruction and/or interfere with student

attention and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a corrective

response, and a classroom-based consequence (e.g., loss of student points or

privileges, a classroom time-out, a note or call home, completion by the

student of a behavior change plan).

After

the consequence is over, and guided by the teacher, the student must positively

practice the appropriate behavior that the student should have done and did not

do (hence, requiring the consequence) at least three times as soon as possible.

_

_ _ _ _

Intensity

III (Persistently Disruptive or Antisocial) Behavior:

Behavior problems in the classroom that significantly (as in a single incident)

or persistently (as in multiple incidents that increase in severity over time)

disrupt classroom instruction or engagement, or that involve antisocial acts

toward adults or peers.

These

inappropriate behaviors require some type of out-of-classroom response (e.g., a

time-out in another teacher’s classroom, removal to a school “student

accountability room,” an office discipline referral), and a consequence that

involves the classroom teacher (even if, for example, an administrator is

involved)—so that the student remains accountable to the teacher and the

classroom where the behavior occurred.

The

consequence could be followed by a restitutional pay-back (e.g., an apology,

cleaning up/repairing damaged property or a messed-up classroom, community

service), and should be followed by the positive practice of the appropriate

behavior described in Intensity II above.

If

it is believed or apparent that the inappropriate behavior is not a

discipline problem but a social, emotional, behavioral, or psychoeducational

problem, the student should be referred to the school’s Multi-Tiered

Services (Child Study, Student Services) Team for assessments to determine the

root cause(s) of the problem, and a resulting behavioral intervention plan that

specifies the services, supports, strategies, or interventions that are both

linked to the assessment results and needed to ameliorate the problem.

_

_ _ _ _

Intensity

IV (Severe or Dangerous) Behavior: These involve extremely

antisocial, damaging, and/or dangerous behaviors—on a physical, social, or

emotional level—that are typically cited and described in a District’s Student

Code of Conduct handbook. These inappropriate behaviors require an immediate

administrative referral and response (e.g., a parent conference, suspension, or

expulsion), followed (at times) by additional consequences, restitutional

requirements, and (once again) positive practice sessions.

While

an administrator may, by Code, need to suspend a student, if she or he believes

that the offense is not a discipline problem but a social, emotional, or

behavioral problem, the student—as in the Intensity III description

above—should be referred into the school’s Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

process.

_

_ _ _ _

As noted, relative to

disproportionality, when teachers consistently use the Intensity I, II, and III

areas of the Matrix for all students, disproportionality is decreased or

eliminated. This often occurs because the Matrix specifically discriminates

between annoying (Intensity I) and disruptive behavior in the classroom

(Intensity II)—explicitly identifying the different responses that facilitate

students’ change of behavior.

When Administrators additionally

hold teachers accountable for using the Matrix appropriately and consistently with

all students, once again, disproportionality is effectively addressed.

When implementing the Behavioral

Matrix process, schools need to use it with specific peer groups. This is

because some peer groups have more social power, reinforcement, or influence

over some individual students— reinforcing their inappropriate behavior and

undermining school and classroom management. Here, the incentives and

consequences built into the Matrix may need to be modified—both for the individual

students and the peer groups involved.

_ _ _ _ _

Taken altogether, the Behavioral

Matrix increases the probability that all students—including students of

color—demonstrate the appropriate interpersonal, social problem-solving,

conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and

coping skills described and taught in the second component above.

When all students—including

students of color—decide to demonstrate inappropriate behavior, the Behavioral

Matrix provides a predictable, but flexible and strategic, roadmap of proven

practices that are focused on holding students accountable for their behavior,

while motivating them to make a better choice the next time.

For teachers, the Behavioral

Matrix also provides them a roadmap, but it especially addresses what needs to

occur when students demonstrate Intensity I of II inappropriate behavior.

For administrators, the

Behavioral Matrix provides guidance as to how to address serious student

inappropriate behavior, and what to do when teachers send inappropriate

“discipline” referrals to the office.

Over time, the Behavioral Matrix

process helps schools and staff to discriminate and effectively address

disciplinary problems and—from a multi-tiered perspective—social, emotional,

and behavioral problems.

We have published an extensive

number of resources that help schools to effectively develop and successfully

implement the Behavioral Matrix process. For example, you may be interested in

our Monograph:

Developing School Discipline Codes that Work: Increasing

Student Responsibility while Decreasing Disproportionate Discipline Referrals

For more information:

[CLICK HERE

for Behavioral Matrix RESOURCES]

_ _ _ _ _

Consistency and Fidelity

Consistency is a process. It

would be great if we could “download” it into all students and staff. . . or

put it in their annual flu shots. . . but that’s not going to happen.

Consistency needs to be “grown”

experientially over time and, even then, it needs to be sustained in an ongoing

way. It is grown through effective strategic planning with detailed

implementation plans, good communication and collaboration, sound

implementation and evaluation, and consensus-building coupled with constructive

feedback and change.

It’s not easy. . . but it is

necessary for school success. And it is especially important when

working with students of color—who

[CLICK HERE for the Full Blog Version of How to Help Staff to be More Consistent]

_ _ _ _ _

Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The last of the evidence-based,

interdependent components that districts and schools need at the center of

their disproportionality recipe involve three “special situations”—the last of

which requires a sound multi-tiered system of supports.

The first Special Situation

focuses on the multiple settings in a school. Here, schools need to plan for

student behavior and interactions not just in the classroom, but also in the

common areas of the school—for example, the hallways, bathrooms, buses,

cafeteria, and the playgrounds or common gathering areas.

The second Special Situation

focuses on the impact of peer groups as psychosocial influencers, and their

relationship to teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical

aggression (fighting).

The third Special Situation

focuses on the fact that some student behavior occurs due to significant or

intense idiosyncratic situations or circumstances that are not disciplinary in

nature, but are part of their social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health

make-up. As discussed earlier, these students often need multi-tiered strategic

(Tier 2) or intensive (Tier 3) services, supports, strategies, or interventions

that are based on functional or diagnostic assessments that determine the root

causes of the students’ challenging behavior.

Examples of some of the triggers

or causes of these social, emotional, and/or behavioral (not disciplinary)

challenges include:

- Physical, Biological,

Physiological, Genetic, Neurological issues

- Significant stresses

or traumas

- Dysfunctional home

and family situations

- Poverty or Economic

stresses

- Significant Life

Changes or Events

We know the students of color are

at-risk in a number of the areas above. Indeed, this fact has been reinforced

especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[CLICK HERE for the Full Blog Version of these Three Special Situations and their Relationship to Disproportionality]

We have discussed the

evidence-based, effective characteristics of a school-level multi-tiered system

of support process in a number of past Blogs.

An excellent resource—that we

used to guide districts’ and schools’ MTSS processes through our work at the

Arkansas Department of Education for 13 years—is:

A Multi-Tiered Service and Support Implementation

Guidebook for Schools: Closing the Achievement Gap

[CLICK

HERE to Review this Resource]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

This two-part Blog Series was

dedicated to helping districts and schools to successfully eliminate

disproportionate discipline referrals and (punitive) actions for students of

color.

In Part I of the Series, we

presented a definition of “racism,” and talked about Critical Race Theory. We

did this to emphasize that (a) the disproportionate disciplinary treatment of

students of color—especially Black students (as well as students with

disabilities)—has existed for decades, and that (b) initiatives to eliminate

disproportionality should not be linked to the recent politicized conversation

involving Critical Race Theory.

Relative to the latter area, we

objectively reviewed the current information regarding Critical Race Theory and

its presence in America’s classrooms. We expressed concerns about the impact

that legislative and other policy-level actions—focused on restricting or

eliminating the discussion of Critical Race Theory in schools—might have on

teachers and students. And, we recommended that educators avoid wasting their

time by looking past the Critical Race Theory politics and debate and, instead,

focus directly on how to eliminate the disproportionate disciplinary referrals

and actions against students of color—a long-standing result of racial bias in

our schools.

Part I then discussed six

different approaches that have been implemented in the past to address

school-level disciplinary disproportionality—explaining why they have not

worked and, hence, why they should be avoided in the future.

In this Part II, we addressed the

six reasons/flaws from Part I by providing effective practices and solutions to

decrease or eliminate disproportionality.

As part of this discussion, we

directly addressed and dismissed an embedded issue in many of the race-based

laws passed by different states during this year’s legislative sessions: the

use of (especially, one-session in-service) anti-bias or diversity training

with school staff members. Relative to disproportionality, however, we still

clearly stated that staff who are specifically motivated by explicit bias and

overt prejudice should be held directly accountable for discriminatory

behavior, and that the recent state laws have not changed this professional

(for administrators) responsibility.

The remainder of this Blog:

- Described five interdependent psychoeducational components

and their specific, embedded practices (addressing Blog Part I’s Flaw #1); that

are

- Organized within a strategically-implemented,

evidence-based, multi-tiered professional development and coaching-centered

whole-school initiative (addressing Flaw #2); that focuses on

- Teaching students—from preschool through high

school— specific, observable, and measurable social, emotional, and behavioral

self-management skills (addressing Flaws #3 and 5).

- We then advocated the use of a data-based

problem-solving process—when students demonstrate frequent, persistent,

unresponsive, significant, or extreme levels of inappropriate, disruptive,

unpredictable, antisocial, or dangerous behavior—to objectively identify the

root causes of the behavior, and to discriminate discipline problems from

social, emotional, behavioral, and/or mental health problems. . . so that

- The assessment results can be linked to the

strategic or intensive multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, or

interventions that will eliminate the student problem and replace it—once

again—with appropriate behavior (addressing Flaw #6).

Using the metaphor of a Master

Chef who needs an excellent recipe and well-honed technical skills to prepare a

world-class meal, the five interdependent psychoeducational components needed

and discussed to eliminate disproportionality were:

- Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climates

- Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skill Instruction

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The inherent principle grounding

the evidence-based approach to disproportionality is:

- When all students (including students of color) are taught

(in developmentally, culturally, and pedagogically-sound ways—from preschool

through high school), and when they have mastered and can apply specific and

scaffolded interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and

resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills. . . and

- When they are prompted, motivated, and held accountable for

using these skills in all school settings and circumstances. . .

- They will consistently demonstrate appropriate, prosocial

interactions. . . such that

- The need to need a disciplinary referral to the principal’s

office will become moot.

In addition, as teachers, support

staff, and administrators design, conduct, and apply this process, they will

develop more intimate relationships with students of color that will help them

to understand the backgrounds and social contexts of these students. Thus, when

annoying or disruptive inappropriate behavior occurs with these same students

of color, they can more easily to move into a self-management problem-solving

mode—reacting more to the person than the person’s race.

_ _ _ _ _

As always, I hope that this

Series was useful to you, and always look forward to your comments. . . whether

on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you in any of the components

or multi-tiered areas discussed above, know that I am constantly working with

districts and schools— virtually and on-site—in this important area. I am always

happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help

you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students.

As your school year enters the

new school year, please accept my best wishes for a safe and productive one. .

. one complete with active and positive student engagement, learning, and

success.

Best,

Howie

[CLICK HERE for the Full Blog Version of this Discussion]