It’s Not About the Plan, It’s About What’s IN the Plan: The Most Frequently Recommended Strategies Do Not Work

[CLICK HERE to read this on my Blog Page]

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Despite the Pandemic, schools are opening, and I am on the road.

Indeed, I spent the entire week in two school districts helping them to implement the successful, award-winning, and evidence-based SEL/Positive Behavior Support strategies that I developed over 30 years ago with Project ACHIEVE (www.projectachieve.info) . . . and that I continue to use and refine across the country.

For those who have never worked with me, these are not your “typical” SEL/PBS strategies. . . and they are not driven by the “special education orientation” that is present in most federal- or state-driven SEL or PBIS frameworks.

These strategies are based on the cognitive-behavioral psychology of individual students and staff; the social and ecological psychology of classrooms and groups; the learning and emotional psychology of children, adolescents, and adults; and the organizational and systems psychology needed by schools and districts.

And, in a multi-tiered context, they work because I use evidence-based blueprints that are tailored to student, staff, school, and system needs using a data-based problem-solving approach. In other words, the blueprints are custom-fit to the problems that individual schools and districts want to solve.

_ _ _ _ _

One of the problems that my Blogs have discussed over the last two months—in a three-part Series—was the disproportionate discipline referral and action rates experienced by students of color. Below are links to the three Blogs in this Series.

July 31, 2021 Blog

The Critical Common Sense Components Needed to Eliminate Disproportionate School Discipline Referrals and Suspensions for Students of Color: This is NOT About Critical Race Theory—But We Discuss It (Part I)

_ _ _ _ _

August 14, 2021 Blog

The Components Needed to Eliminate Disproportionate School Discipline Referrals and Suspensions for Students of Color Do Not Require Anti-Bias Training: Behind Every Iron Chef is an Iron-Clad Recipe (Part II)

_ _ _ _ _

August 28, 2021 Blog

Disproportionate School Discipline, and How Long-Term Suspensions Don’t Work and Don’t Improve Classroom Conditions When Students are Gone (An Unexpected Part III). The Numbers Don’t Lie, But Are They Enough to Prompt Change?

_ _ _ _ _

And while I wasn’t planning to revisit this topic for a while, an important study was published this week that addressed disciplinary disproportionality— with both students of color and students with disabilities... a study that reinforced a number of themes and assertions in these three integrated Blogs.

But most important, this study—which was methodologically well-designed— involved analyzing the effects of interventions implemented by 41 high-disproportionality status school districts to decrease their disproportionate student disciplinary referrals patterns. The results, spanning a five year period of time, were compared to those from 41 matched but low-disproportionality districts.

The study’s results clearly demonstrated that:

The most common national strategies or “interventions” used to eliminate the disproportionate discipline referrals for students of color and with disabilities did not decrease or eliminate the disproportionality.

Thus, one of the necessary conclusions is:

The use of these specific strategies or “interventions” must be re-considered and retired, and other approaches that have demonstrated success need to be embraced and implemented.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Story Behind the Study

This study was published by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Educational Sciences through its National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance and prepared by the Regional Education Laboratory Midwest administered by the American Institutes for Research.

The Effect of Discipline Reform Plans on Exclusionary Discipline Outcomes in Minnesota

The study began when, in 2017, the Minnesota Department of Human Rights (MDHR) identified 43 school districts in the state that were out-of-compliance relative to their disproportionate use—when compared to White and non-disabled students—of exclusionary discipline practices (suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions) with American Indian and Black students, and students with disabilities.

The study examined the use of these exclusionary discipline practices for the 2014-2015 through 2018-2019 school years, and the impact of the Discipline Reform Plans that they (a) developed during the 2017-2018 school year, and (b) implemented during the 2018-2019 school year to remediate the problem.

According to the Study:

MDHR identified these 43 local education agencies based on the following criteria:

- Overall suspension and expulsion rates.

- Suspension and expulsion rates of all racial/ethnic minority students.

- Suspension and expulsion rates of American Indian and Black students.

- Suspension and expulsion rates of students in special education programs.

- Rate of suspensions and expulsions determined by MDHR to be assigned for a subjective infraction (actions and behaviors such as disobedience) rather than an objective infraction (actions and behavior such as bringing a weapon to school or fighting.

Of the 43 identified local education agencies, 41 agreed to create a Discipline Reform Plan, and the MDHR agreed not to pursue legal action against those local education agencies that participated. These 41 districts’ disproportionality data (and 2018-2019 results) were compared with 41 districts that were demographically matched to the original 41, but that had low disproportionality rates with students of color and with disabilities.

Critically, in addition to developing and implementing their Plans, the Districts also needed to agree that they would:

- Faithfully implement and measure the effectiveness of strategies such as restorative justice, positive behavioral intervention, and Innocent Classroom (a program that provides professional development to teachers to address racial bias).

- Collaborate with other identified local education agencies to develop best practices to reduce exclusionary discipline actions and implement cultural competency and corrective action strategies.

- Develop meaningful ways for students, parents, teachers, and the broader community to engage and give input on discipline reform.

- Develop a process to collect and analyze data from student discipline referrals to understand the challenges that students face, the needs of teachers, and where implicit bias exists.

- Limit the role of police liaison officers in school buildings to legal and safety matters rather than student misbehavior.

- Analyze current policies and practices on student discipline

- Report progress to MDHR twice each year for three years.

Thus, there was a built-in implementation integrity/fidelity provision to both the Plans and this Study.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

What Strategies or Interventions Were Used in the Districts’ Disproportionality Plans

The 41 participating districts used a wide variety and mixture of different strategies and/or interventions. In addition, the Discipline Reform Plans also varied in how specifically they described their approaches, implementation steps, evaluation processes, and formative results. One reason for this variability was that the MDHR did not provide a template nor training for the content of the plans, or their execution and evaluation.

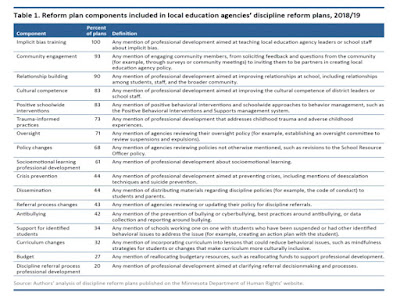

Below is a table from the Report that identifies how the Study’s authors defined the different strategies and interventions such that they were able to tabulate how frequently they were used.

In the end, each district’s Discipline Reform Plan included at least seven and up to 18 different strategies or interventions (see Figure 1). While Implicit Bias Training appeared in all 41 plans, and Community Engagement appeared in 38 plans, providing professional development on the discipline referral process was the least common reform—appearing in eight plans.

The Results? Disproportionality Did Not Decrease or Disappear

The Report summarized (with some editing to improve clarity) the study’s results as follows:

[CLICK HERE for the Details and Figures related to these Results]

- Result 1: Students of Color. Differences in exclusionary discipline action rates by race/ethnicity were larger in the Districts with Discipline Reform Plans than in the Comparison low-disproportionality Districts

_ _ _ _ _

- Result 2: Students with Disabilities. In the 2018-2019 school year, the discipline action rate decreased slightly for students with disabilities in the Districts with Discipline Reform Plans.

However, the difference in discipline action rates between students with disabilities and students not in special education still remained larger in districts with Discipline Reform Plans than in the Comparison low-disproportionality Districts.

_ _ _ _ _

- Result 3: The Impact of a Discipline Reform Plan. Creating a Discipline Reform Plan was not associated with a statistically significant decline in exclusionary disciplinary actions in 2018-2019, after accounting for student and district characteristics and prior trends in exclusionary discipline actions.

[CLICK HERE for the Details and Figures related to these Results]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary and Implications

Once again, the study’s results clearly demonstrated that:

The most common national strategies or “interventions” used to eliminate the disproportionate discipline referrals for students of color and with disabilities did not decrease or eliminate the disproportionality.

Thus, one of the necessary conclusions is:

The use of these specific strategies or “interventions” must be re-considered and retired, and other approaches that have demonstrated success need to be embraced and implemented.

_ _ _ _ _

More specifically (looking at Table 1), this study reinforces numerous research-to-practice conclusions (made in previous Blogs) where it is clear that the following strategies, frameworks, or programs have not been comprehensively field-tested, objectively validated, and do not demonstrate the efficacy for use in schools and districts nationwide:

- Implicit Bias Training

- PBIS

- Trauma-Informed Practices

- Policy Changes

- Socio-emotional Learning (SEL) Professional Development

- Anti-bullying

- Curriculum Changes (including Mindfulness)

_ _ _ _ _

In addition, the following implications embedded in this study need to be considered:

- Discipline Reform Plans (or the equivalent) must be effectively written (and implemented) so that they specifically include the necessary SMART goals, professional development and follow-up technical assistance training, formative and summative fidelity and outcome evaluations, implementation resources and timelines, staffing and supervision, and strategic integrations into other school and district activities.

_ _ _ _ _

- Different strategies and interventions should not be randomly “stacked” into Discipline Reform Plans (or the equivalent) until their compatibility, efficacy, and time- and cost-effectiveness had been field-tested and validated.

The point here is that the 41 districts in the Study used a multitude of strategies and interventions, and it is possible that some of these interventions were redundant or, worse, that they worked at cross-purposes to one other. . . thus undermining their potential effects and the student and staff outcomes.

It is also possible that the districts, in the course of one year, were trying to implement too much too soon.

_ _ _ _ _

- The districts (and the Study) should have disaggregated the “Students with Disabilities” cohort to identify the specific disabilities (of the 13 different ones identified by law) of the students involved, and whether they had appropriate multi-tiered social, emotional, and behavioral services, supports, strategies, and interventions written into their IEPs.

Nationally, many school staff—including related service professionals—have not been effectively trained in the many well-established social, emotional, and behavioral interventions present in the research.

In addition, they often have not been trained in the data-based, functional assessment, problem-solving processes needed to identify the root causes of these students’ challenges, so that their assessment results can be linked to the highest probability of success services and interventions.

Students with disabilities who have social, emotional, or behavioral challenges that are related to their disabilities should not receive “discipline.” Instead, they should receive the services and interventions needed to decrease or eliminate the behaviors of concern. Simultaneously, classroom teachers should receive the consultation and support needed to help implement these interventions in their classrooms, increasing their understand the effects of the students’ disabilities.

_ _ _ _ _

I hope that the review of this Study—and its implications—is useful to you. And I always look forward to your comments. . . whether on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you, your colleagues, your school, or your district (a) to address the disproportionality present in your setting; (b) to improve your services and supports for students of color or with disabilities; or (c) to increase the availability of research-supported classroom management strategies or strategic/intensive social, emotional, or behavioral interventions, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Know that I am always available to you—virtually and on-site—to address your needs. And, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and potential directions on behalf of your students.

Best,

Howie